Management of necrotizing pancreatitis is challenging and has been associated with an overuse and misuse of antibiotics.1 Most patients with sterile necrotizing pancreatitis can be managed without intervention (ie, necrosectomy or percutaneous drainage) and without antibiotics.2-10 Additionally, randomized controlled trials have failed to show the benefit of prophylactic antibiotics in the setting of acute and necrotizing pancreatitis.2,3

In the setting of infected necrotizing pancreatitis, however, antibiotics are universally recommended.4-12 Diagnosis of infected necrotizing pancreatitis is difficult as the inflammatory process seen in severe pancreatitis may be indistinguishable from infection. Clinical signs and symptoms of infection (ie, persistent fever, abdominal pain, elevated procalcitonin) and imaging showing gas in peripancreatic tissues are considered evidence of infected necrotizing pancreatitis (Table 1).6-8,11,13

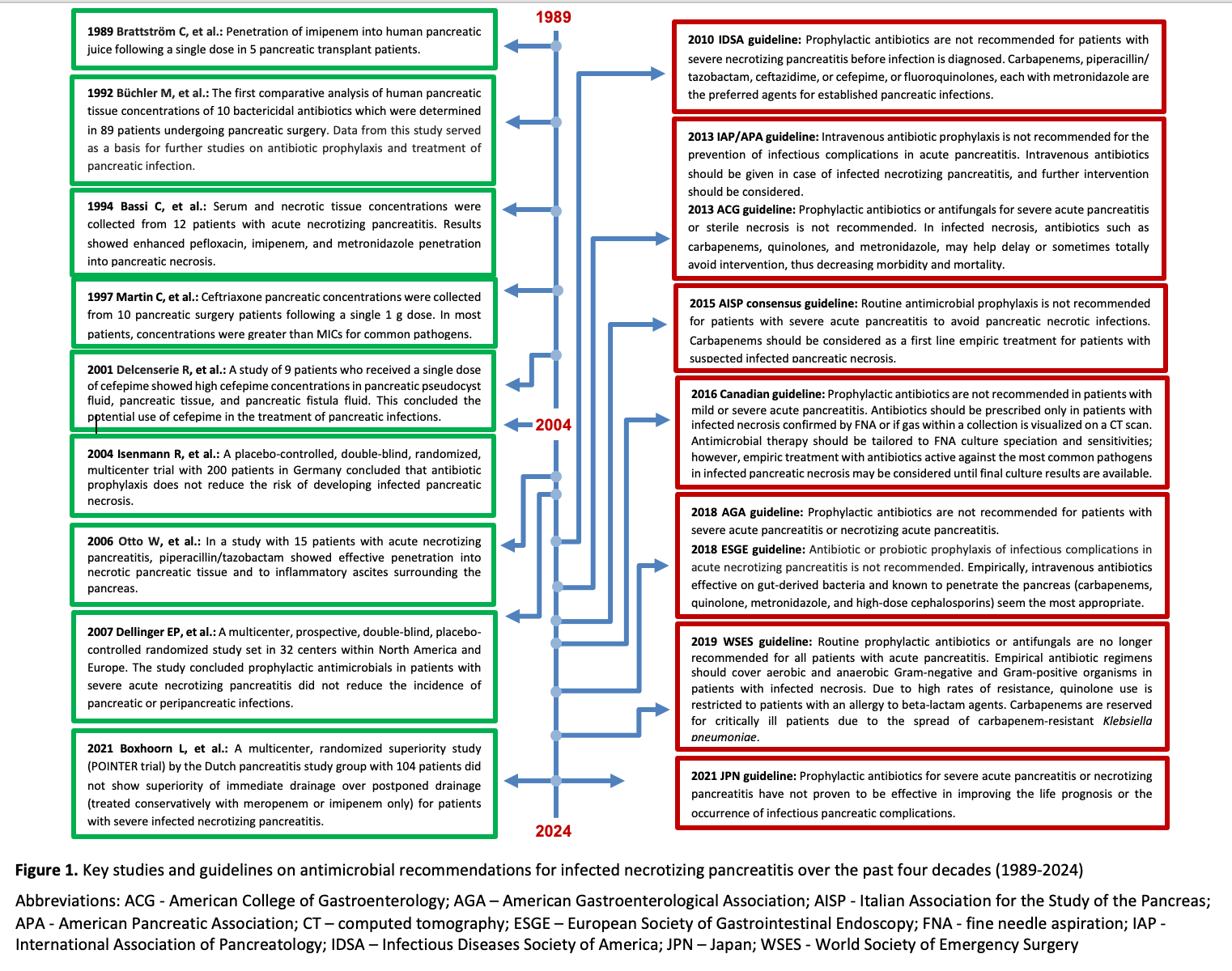

Once a diagnosis of infected necrotizing pancreatitis is made, antibiotics should be started as part of a comprehensive treatment strategy that includes hydration, pain control, nutritional support, and surgical intervention when necessary. Multiple guidelines recommend the use of carbapenems as treatment of infected necrotizing pancreatitis largely based on pharmacokinetic data from the 1980s and 1990s demonstrating imipenem’s ability to penetrate pancreatic tissue.14-16 However, non-carbapenem beta-lactams (ie, ceftriaxone, cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam) may also be considered as part of the pancreatic treatment arsenal based on pharmacokinetic data published later demonstrating adequate pancreatic concentrations.17

Antibiotic Choice: What do the Guidelines Say?

Various national and international guidelines have addressed the management of infected necrotizing pancreatitis (Figure 1).4-12,14-16,18,19 Most suggest utilizing antibiotics known to penetrate pancreatic necrosis.5,8,10 The 2013 American College of Gastroenterology Guideline (ACG) on the Management of Acute Pancreatitis recommends carbapenems, quinolones, and metronidazole, a conditional recommendation based on low quality of evidence.5 Interestingly, this same guideline also mentions that antibiotics shown to penetrate pancreatic tissue in clinical trials include carbapenems, quinolones, metronidazole, and high-dose cephalosporins. The 2018 European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline also includes high-dose cephalosporins as a treatment option for infected necrotizing pancreatitis.8 The 2019 World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) guidelines recommend that carbapenems should be used only in very critically ill patients due to the spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae.10

The Ideal Antibiotic: What Does the Data Say?

Ideal antibiotics for the management of infected necrotizing pancreatitis include those with activity against gastrointestinal commensal bacteria and penetrate necrotic pancreatic tissue.8 Pharmacokinetic characteristics favorable for penetrating necrotic pancreatic tissue include high lipophilicity and a large volume of distribution. Early human studies investigating antibiotic penetration into pancreatic tissues often included metronidazole, quinolones, and carbapenems, which all demonstrated penetration of necrotic pancreatic tissue and achieved concentrations above typical minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for most pathogens of concern.14-16 In later years, cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam, and ceftriaxone were also investigated for their abilities to penetrate necrotic pancreatic tissues (Table 2).

In 1997, Ceftriaxone pancreatic concentrations were collected from 10 pancreatic surgery patients following a single 1g dose.20 In most patients, concentrations were greater than MICs for common pathogens. In 2001, cefepime pancreatic concentrations were measured from nine patients who received a single 2g dose of cefepime.21 Results showed high cefepime concentrations in pancreatic pseudocyst fluid, pancreatic tissue, and pancreatic fistula fluid and concluded potential use of cefepime in the treatment of pancreatic infections. Additional studies have also shown adequate cefepime pancreatic concentrations.22,23 In 2006, piperacillin-tazobactam pancreatic concentrations were measured from 15 patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis, which showed effective penetration into necrotic pancreatic tissue and to inflammatory ascites surrounding the pancreas.18

Conclusion

In the setting of infected pancreatitis, antibiotics should be utilized as part of a multimodal treatment strategy. Carbapenem-sparing regimens include piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime plus metronidazole, or ceftriaxone plus metronidazole. Fluoroquinolones may be considered as oral step down for treatment; however, they should be reserved for select cases due to the prevalence of resistance and potential collateral damage.

References

- Timmerhuis HC, van den Berg FF, Noorda PC, van Dijk SM, van Grinsven J, Weiland CJ, Umans DS, Mohamed YA, Curvers WL, Bouwense SA, Hadithi M. Over-and Misuse of Antibiotics and the Clinical Consequence in Necrotizing Pancreatitis: An Observational Multicenter Study. Annals of Surgery. 2023 Jan 3:10-97.

- Isenmann R, Rünzi M, Kron M, et al; German Antibiotics in Severe Acute Pancreatitis Study Group. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gastroenterology. 2004 Apr;126(4):997-1004. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.050.

- Dellinger EP, Tellado JM, Soto NE, et al. Early antibiotic treatment for severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Surg. 2007 May;245(5):674-83. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250414.09255.84.

- Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, et al. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Jan 15;50(2):133-64. doi: 10.1086/649554.

- Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Sep;108(9):1400-15; 1416. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.218.

- Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013 Jul-Aug;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.07.063.

- Greenberg JA, Hsu J, Bawazeer M, et al. Clinical practice guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Can J Surg. 2016 Apr;59(2):128-40. doi: 10.1503/cjs.015015.

- Arvanitakis M, Dumonceau JM, Albert J, et al. Endoscopic management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines. Endoscopy. 2018 May;50(5):524-546. doi: 10.1055/a-0588-5365.

- Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, Falck-Ytter Y, Barkun AN; American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on Initial Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1096-1101. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.032.

- Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2019 Jun 13;14:27. doi: 10.1186/s13017-019-0247-0.

- Pezzilli R, Zerbi A, Campra D, et al. Consensus guidelines on severe acute pancreatitis. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2015;47(7):532-43. doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2015.03.022.

- Takada T, Isaji S, Mayumi T, et al. JPN clinical practice guidelines 2021 with easy-to-understand explanations for the management of acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022 Oct;29(10):1057-1083. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.1146.

- van Baal MC, Bollen TL, Bakker OJ, et al; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. The role of routine fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Surgery. 2014 Mar;155(3):442-8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.10.001.

- Brattström C, Malmborg AS, Tydén G. Penetration of imipenem into human pancreatic juice following single intravenous dose administration. Chemotherapy. 1989;35(2):83-7. doi: 10.1159/000238652.

- Büchler M, Malfertheiner P, Friess H, et al. Human pancreatic tissue concentration of bactericidal antibiotics. Gastroenterology. 1992 Dec;103(6):1902-8. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91450-i.

- Bassi C, Pederzoli P, Vesentini S, et al. Behavior of antibiotics during human necrotizing pancreatitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994 Apr;38(4):830-6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.38.4.830.

- Maguire C, Agrawal D, Daley MJ, Douglass E, Rose DT. Rethinking Carbapenems: A Pharmacokinetic Approach for Antimicrobial Selection in Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2021 Jul;55(7):902-913. doi: 10.1177/1060028020970124.

- Otto W, Komorzycki K, Krawczyk M. Efficacy of antibiotic penetration into pancreatic necrosis. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8(1):43-8. doi: 10.1080/13651820500467275.

- Boxhoorn L, van Dijk SM, van Grinsven J, et al; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Immediate versus Postponed Intervention for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021 Oct 7;385(15):1372-1381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100826.

- Martin C, Cottin A, François-Godfroy N, et al. Concentrations of prophylactic ceftriaxone in abdominal tissues during pancreatic surgery. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997 Sep;40(3):445-8. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.3.445.

- Delcenserie R, Dellion-Lozinguez MP, Yzet T, et al. Pancreatic concentrations of cefepime. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001 May;47(5):711-3. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.5.711.

- Sağlamkaya U, Mas MR, Yaşar M, Simşek I, Mas NN, Kocabalkan F. Penetration of meropenem and cefepime into pancreatic tissue during the course of experimental acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2002 Apr;24(3):264-8. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200204000-00009.

- Papagoras D, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Kanara M, et al. Pancreatic concentrations of cefepime in experimental necrotizing pancreatitis. J Chemother. 2003 Feb;15(1):43-6. doi: 10.1179/joc.2003.15.1.43.

- Roberts EA, Williams RJ. Ampicillin concentrations in pancreatic fluid bile obtained at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1979 Sep 1;14(6):669-72.