Earlier this month, the first human case of avian influenza A (H5N1 this year) in the United States was reported.1-3 The person became infected following contact with dairy cows presumed to be infected with avian influenza. The person’s primary symptom has been conjunctivitis and is being treated with an antiviral. The person was told to isolate while in recovery. As of today, there is just 1 isolated case in Texas.

It remains unclear as to how the Texas case happened. Richard Webby, PhD, director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds and Department of Host-Microbe Interactions, Division of Virology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, says that if you make the assumption there were sick birds nearby, somehow cows got infected and then likely passed the virus along to the person in Texas.

Overall these are wild, migratory birds that might be traveling great distances and could be infected from hosts thousands of miles away.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the general public should avoid unprotected exposure to sick or dead animals including wild birds, poultry, other domesticated birds, and other wild or domesticated animals (including cattle), as well as with animal carcasses, raw milk, feces, litter, or materials contaminated by birds or other animals with confirmed or suspected HPAI A(H5N1)-virus infection.3,4

People should not prepare or eat uncooked or undercooked food or related uncooked food products, such as unpasteurized (raw) milk, or products made from raw milk such as cheeses, from animals with confirmed or suspected HPAI A(H5N1)-virus infection.

Webby has been involved in research around avian influenza ecology, influenza vaccination, and influenza virus pathogenicity. He explains transmission is a 2-step process where it goes first from birds to humans, and then from human to human. It is the latter that is the more serious, concerning threat.

“When we think about this from a virus perspective, there does seem to be 2 different barriers to this virus, getting into humans—that’s first,” Webby stated. “So, bird to human is a little bit lower [transmission] than that second, which is the human-to-human transmission. But now, that’s why we get a little bit worried when we see mammals infected with this virus…In that environment, that’s where we think the virus is going to get the most chances to make the changes, it needs to successfully go human to human.”

And when the jump goes from zoonotic then to human-to-human transmission there are mutations involved in the virus possibly making it more transmissible and vulnerable to a pandemic scenario, says Webby.

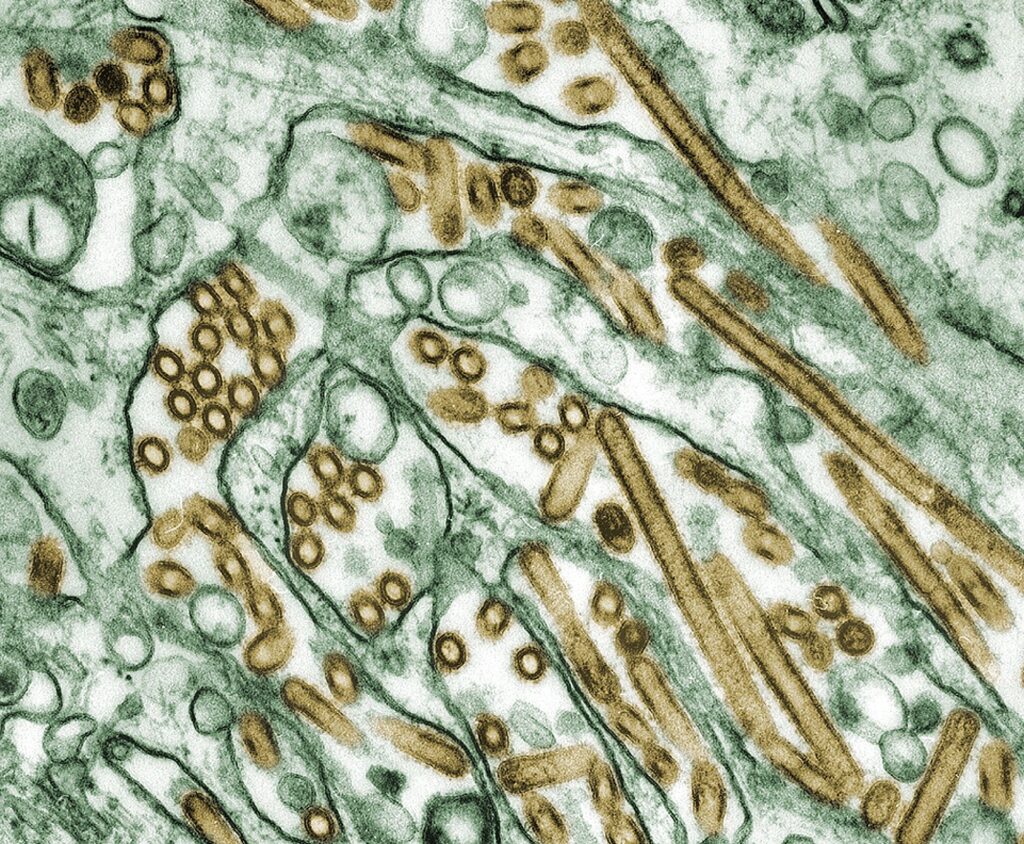

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (seen in gold) grown in MDCK cells (seen in green).

Photo Credit: Cynthia Goldsmith Content Providers: CDC/ Courtesy of Cynthia Goldsmith; Jacqueline Katz; Sherif R. Zaki

Vaccines and Treatment

He notes some H5N1 vaccines are being stockpiled by the US government in case of a human outbreak.

“The absolute use of those would be detailed in pandemic plans, but you can imagine if this virus started to go human-to-human, I think the first line responders and healthcare workers might be first in line to receive this,” Webby said. “I mean, if this virus continues to circulate in cows, maybe you can make an argument for people in close contact with those infected herds as well. But I think that’s a little less likely. The risk is still very low.”

“We [have] got to put all of this into a little bit of perspective. We are seeing a lot of activity of this particular virus in animal populations, but it is still low risk to humans.”

And for those who do become infected with H5N1, some of the existing influenza therapies including oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) are efficacious against the virus, explains Webby.

He says timing is important as an earlier intervention will help with optimal outcomes and the quicker alleviation of symptoms.

“I think the most important message is anyone who thinks perhaps, ‘I’ve been exposed to this virus, and I started to come down with symptoms,’ whether that be respiratory symptoms, or maybe with this virus, even conjunctivitis, go and see a doctor really early on because that’s the best chance you’ve got for those medications to actually work.”

References

1. Parkinson J. Avian Flu Reported in First American This Year. Contagion. April 2, 2024. Accessed April 9, 2024.

https://www.contagionlive.com/view/avian-flu-reported-in-first-american-this-year

2. Health Alert: First Case of Novel Influenza A (H5N1) in Texas, March 2024. Texas Department of State Health Services press release. April 1, 2024. Accessed April 9, 2024. https://www.dshs.texas.gov/news-alerts/health-alert-first-case-novel-influenza-h5n1-texas-march-2024

3. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus Infection Reported in a Person in the U.S. CDC press release. April 1, 2024. Accessed April 9, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/p0401-avian-flu.html

4. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus in Animals: Interim Recommendations for Prevention, Monitoring, and Public Health Investigations. Influenza. CDC. Last reviewed March 29, 2024. Accessed April 9, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/hpai/hpai-interim-recommendations.html