This article originally appeared on our sister site, Contemporary Pediatrics.

Cases of measles continue to be reported in Delaware, New Jersey, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Washington State, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) News report.1

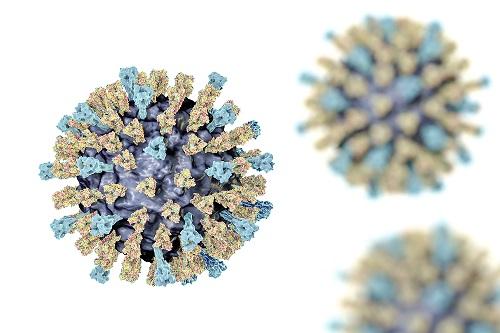

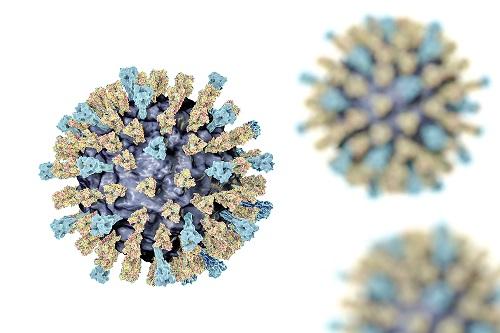

Transmitted through contact of droplets or airborne spread via breathing, coughing, or sneezing from an infected individual, measles can remain in the air for up to 2 hours.1

“[These reports are] not really surprising given the decrease in vaccination rates that have been occurring since the pandemic,” said Tina Tan, MD, FAAP, FIDSA, FPIDS, editor-in-chief, Contemporary Pediatrics; professor of pediatrics, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University; pediatric infectious diseases attending, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

“This is not new and demonstrates what is known, in that if vaccination rates do not stay at a level that is protective, outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases will occur,” said Tan.

The acute viral respiratory illness can be characterized by fever as high as 105 degrees Fahrenheit and malaise, coryza, cough, and conjunctivitis, a pathognomonic enanthema followed by a maculopapular rash, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2

The CDC states that up to 9 out of 10 susceptible persons with close contact to an infected measles patient will develop the infectious disease. Infants and children aged younger than 5 years are at high-risk for severe illness and further complications from measles.2

Routine childhood immunization for the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine is recommended at 12 to 15 months of age for the first dose, with the second coming at ages 4 through 6 years, or at least 28 days after first dose.2

The MMR-varicella (MMRV) vaccine is available to children 12 months through 12 years of age, with 3 months being the minimal interval between doses.2

“Clinicians need to understand that the United States—and multiple other countries around the world—are currently in an environment where vaccination rates have fallen below protective levels given the significant increase in vaccine hesitancy and major decrease in vaccination rates,” Tan said. “Measles and other vaccine preventable diseases need to be on the differential diagnoses of children presenting with signs and symptoms that may be associated with these diseases.”

According to the CDC, evidence of immunity for measles includes at least 1 of the following:2

- One or more doses of a measles vaccine on or after the first birthday for preschool-aged children

- Two doses of a measles vaccine for school-aged children, including college students, health care personnel, and international travelers.

- Laboratory evidence of immunity

- Laboratory confirmation of measles

- Birth before 1957

The AAP report states a CDC study recently revealed that 93% of kindergartners were fully vaccinated against measles in the 2022 to 2023 school year, marking it the third consecutive year that vaccination rates were below the “Healthy People 2030 target of 95%.”1

“There has been a decrease in vaccination rates here in Chicago and other areas of the United States due to an increase in vaccine hesitancy,” added Tan. “There has also been an increase in parents seeking notes of medical and philosophical exemption so that they do not have to vaccinate their children.”

References:

- Jenco M. Measles reported in multiple states; be prepared to take infection-control steps. AAP News. January 24, 2024. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/27983/Measles-reported-in-multiple-states-be-prepared-to?searchresult=1

- For Healthcare Providers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 5, 2020. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html